[Note: I definitely didn’t expect the welcome reception this post has received from so many notable bloggers! Thank you all for your support and compliments. I took a few snapshots and have uploaded them, although I admit they are not of the best quality. I will come up with some better versions of these images when I have more time this week.]

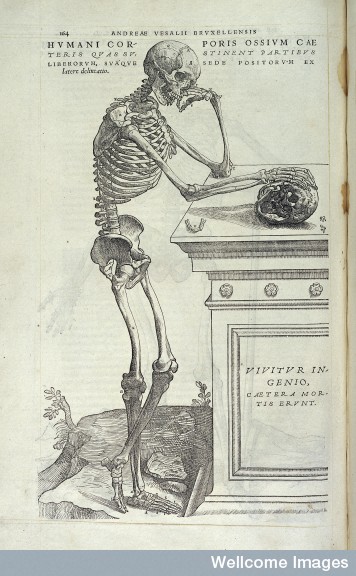

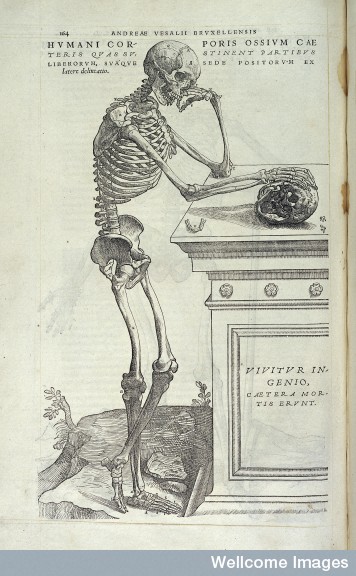

From the Wellcome Images Collection

How many ribs do humans have? Despite it being a fairly straightforward answer, you may get different replies depending on who you ask. Few people will know the exact number (12 pairs), but a surprisingly large amount of people might tell you that while women have a full set, men come up one short. Basic anatomy proves this to be wrong, but then again most people have not studied basic anatomy, so where would such an idea come from?

20: And Adam gave names to all cattle, and to the fowl of the air, and to every beast of the field; but for Adam there was not found an help meet for him.

21: And the LORD God caused a deep sleep to fall upon Adam, and he slept: and he took one of his ribs, and closed up the flesh instead thereof;

22: And the rib, which the LORD God had taken from man, made he a woman, and brought her unto the man.

23: And Adam said, This is now bone of my bones, and flesh of my flesh: she shall be called Woman, because she was taken out of Man.

– Genesis 2:20-23

It almost sounds like a Neo-Lamarckian belief; that because God took a rib from Adam (whether it was just one or one pair, the book does not say) to make Eve in the second Genesis creation story, all men should inherit the trait of missing one rib. In fact, it is possible (even likely) that the “rib” taken from Adam was not one of the bones in his chest at all, but rather a mythical baculum (or “penis bone“), which is present in most mammals but missing in man and a few others. Despite the Bible being opaque on the topic of general anatomy, however, the belief that the number of ribs in men and women are different is widespread and I am often met with astonished faces when I tell people who accept the idea that there is no difference between the sexes in that respect at all. Outside of a widespread unfamiliarity with basic human anatomy, the belief shows us something else; that just as Homo sapiens has evolved, so too have our ideas about ourselves, and vestiges of past beliefs still remain in the skeletal structure of our understanding.

From William Cheselden’s The Anatomy of Bones. This image also graces the cover of my copy of William Paley’s Natural Theology.

Although the Genesis account of the creation of man is probably the most familiar, it is far from being original. The concepts found in the first chapters of the book of Genesis correlate surprisingly closely to earlier beliefs of the Chaldeans and Babylonians, from the differing orders of the two creation accounts to the dispersal at the Towel of Babel. Seeing that the myths from which the Genesis account derive no longer exist in their original form, however, we will start our intellectual foray with the set of beliefs that rails against science even to this day; that humans were specially created by God less than 10,000 years ago, from little more than some dirt and a rib. As alluded to before, the accounts of the creation of humans contradict each other and cannot be reconciled (as many apologists attempt to do) by saying that the account given in Genesis 1 is merely an overview or outline, with Genesis 2 filled in the details.

If we look at Genesis 1, God creates plant life (before the “lights in the firmament”), then life in the water and the air, then all the “beasts” and “creeping things” (of which there are many more than the beasts), and then both sexes of Homo sapiens simultaneously;

27: So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them.

The God of Genesis 2 does things a little differently (perhaps even taking a more pragmatic approach). We are told that because there was “no man to till the ground,” there was no point in creating plants on earth before people. Thus God watered the entire face of the earth and then created man, “planting” the man in Eden. It might be impious to think this way, but whenever I read that verse (Genesis 2:8) I can’t help but imagine a gigantic hand picking up Adam by the scruff of his neck and literally placing him back down in the Garden. Imagery aside, God then populates the Garden with plant life (which in Genesis 1 was long established on earth before Adam came to be), and then decides that it isn’t good to have Adam wandering around Eden by himself. We are told that God then created all the “beasts of the field” and “fowl of the air” and had Adam name them (but neglected to form a proper system of taxonomy or systematics), but no “help mate” was to be found. Then comes to famous rib-story (see above), things finally being set right in Eden, at least until that whole forbidden-fruit business. Despite the strange inconsistencies, in both accounts humans are the crowning achievements of the Creation, told to “subdue” the planet and to reproduce in order to fill it. This idea of trampling nature beneath our heel has resonated with people for thousands of years, although theology has twisted various aspects of Genesis this way and that to suit certain needs.

Indeed, while Adam and Eve were supposed to be the ancestors of all humanity, some groups of people were left out of the picture. Just like certain lower classes of people in other cultures were said to be formed from the “dirt of the body” particular gods, denoting their inferior existence, people with darker skin were deemed to be bearing the “Mark of Cain” or to be “Sons of Ham,” in either case slavery being justified for the sins of the proginator of that line. Thankfully this view has now largely been abandoned, although vestiges of such superstitions remain today (and equality wasn’t even given to these people until the middle of the last century in the United States). Racism and the Biblical justifications for it is another complex issue however, and it is only mentioned here to elucidate the point that even in theology, the origins of man have not always been used for good or just ends.

The first section of the original “March of Progress” from F. Clark Howell’s Early Man

While basic researches into ancient Egypt and other cultures began to show that the chronology determined by Lightfoot, Ussher, and others was far too short to be accurate, our place as a special creation didn’t start to be truly challenged until the remains of ancient peoples unlike ourselves began to be discovered. Fossils found by many cultures had long been thought to be evidence of gods, titans, giants, dragons, and monsters (see Adrienne Mayor’s The First Fossil Hunters), but these remains seemed to be more curiosities or holy relics than the remains of people more ancient than anyone then conceived of. Andrew D. White tells us in his masterwork A History of the Warfare of Science With Theology in Christendom;

In France, the learned Benedictine, Calmet, in his great works on the Bible, accepted [“the doctrine that fossils are the remains of animals drowned at the Flood”] as late as the beginning of the eighteenth century, believing the mastodon’s bones exhibited by Mazurier to be those of King Teutobocus, and holding holding them valuable testimony to the existence of the giants mentioned in Scripture and of early inhabitants of the earth overwhelmed by the Flood.

Even in the 1854 edition of Gideon Mantell’s Medals of Creation, fossil remains of humans are not mentioned because they seemed to be conspicuously lacking. In the “Retrospect” of the book Mantell writes;

But of MAN and his works not a vestige appears throughout the vast periods embraced in this review. Yet were any of the existing islands or continents to be engulphed in the depths of the ocean, and loaded with marine detritus, and in future ages be elevated above the waters, covered with consolidated mud and sand, how different would be the characters of those strata from any which have preceded them! Their most striking features would be the remains of Man, and the production of human art – the domes of his temples, the columns of his palaces, the arches of his stupendous bridges of iron and stone, the ruins of his towns and cities, and the durable remains of his earthly tenement imbedded in the rocks and strata – these would be the “Medals of Creation” of the Human Epoch, and transmit to the remotest periods of time a faithful record of the present condition of the surface of the earth, and of its inhabitants.

This doesn’t mean that the remains of humans were not thought to be found, however. In an earlier chapter on reptiles (being that amphibians were included within the reptiles in Mantell’s work), the author writes;

A celebrated fossil of this class is the gigantic Salamander (Cryptobranchus), three feet in length found at Ceuingen, which a German physician of some note (Scheuchzer) supposed to be a fossil man!

Scheuchzer’s tricky salamander, from the 2nd volume of Mantell’s Medals of Creation.

The view of fossils began to change, however, as creatures were found that could not simply be considered giants, gods, or heroes. A.D. White quotes Dr. Anton Westermeyer’s The Old Testament vindicated from Modern Infidel Objections as follows;

“By the fructifying brooding of the Divine Spirit on the waters of the deep, creative forces began to stir; the devils who inhabited the primeval darkness and considered it their own abode saw that they were to be driven from their possessions, or at least that their place of habitation was to be contracted, and they therefore tried to frustrate God’s plan of creation and exert all that remained to them of might and power to hinder or at least, to mar the new creation.” So came into being “the horrible and destructive monsters, these caricatures and distortions of creation,” of which we have fossil remains. Dr. Westermeyer goes on to insist that “whole generations called into existence by God succumbed to the corruption of the devil, and for that reason had to be destroyed”; and that “in the work of the six days of God caused the devil to feel his power in all earnest, and made Satan’s enterprise appear miserable and vain.”

Indeed, although the first known remains of Megalosaurus were confused to be the enormous testicles of an “Antediluvian Giant,” the rest of the skeletal remains found by Dr. Buckland (and those of Iguanodon found by Mantell) showed that these animals could not be considered to be characters introduced to us in the Biblical narrative of creation or history. While evolution or “transmutation” of species was not yet ready to make its full appearance on the scientific stage, some did recognize the fossils as representing animals long gone, and the concept of extinction that Cuvier did so much to establish became essential to scientific thought and was a great victory over the religious dogma that God would not create a “kind” of animals and then let them be destroyed. This does not mean that other explanations of these remains were not legion, however.

Despite his contributions to marine biology, Philip Henry Gosse published one of the most infamous attempts to reconcile the geologic column with a historically-accurate Genesis account in his 1857 book Omphalos: An Attempt to Untie the Geological Knot. Taking the reader on a painfully protracted tour of creation, the author introduces us to Adam, the prose suggesting that Gosse has persuaded Adam to sit down for a full anatomical evaluation. After detailing certain aspects of Adam’s anatomy (including the ever-problematic navel), Gosse tells us that every bit of Adam’s anatomy tells of a full human life, from gestation to birth to growth, but this is merely a set-up. Gosse writes;

How is it possible to avoid this conclusion? Has not the physiologist irrefragable grounds for it, founded on universal experience? Has not observation abundantly shown, that, wherever the bones, flesh, blood, teeth, nails, hair of man exist, the aggregate body has passed through stages exactly correspondant to those alluded to above, and has originated in the uterus of a mother, it foetal life being, so to speak, a budding out of hers? Has the combined experience of mankind ever seen a solitary exception to this law? How, then, can we refuse the concession that, in the individual before us, in whom we find all the phenomena that we are accustomed to associate with adult Man, repeated in the most exact verisimilitude, without a single flaw-how, I say, can we hesitate to assert that such was his origin to?

And yet, in order to assert it, we must be prepared to adopt the old Pagan doctrine of the eternity of matter; ex nihilo nihil fit. But those with whom I argue are precluded from this, by my first Postulate.

Gosse’s first Postulate being;

If any geologist take the position of the necessary eternity of matter, dispensing with a Creator, on the old ground, ex nihilo nihil fit, – I do not argue with him. I assume that at some period or other in past eternity there existed nothing but the Eternal God, and that He called the universe into being out of nothing.

All such considerations from Gosse, Mantell, and others seem to ignore that remains like, yet unlike, humans were already being discovered during the 19th century. While the most noted discovery of Neanderthals occurred 151 years ago this past week, fossils of hominids we now call Neanderthals were found in 1829 and 1848, A.D. White mentioning unspecified “human remains” being found “as early as 1835 at Cannstadt near Stuttgart” as well. Still, the remains of Neanderthals and stone tools seemed to be too close to Homo sapiens to dissuade advocates of special creation that man had evolved, although scientists were able to confirm that the origins of mankind were probably far older than anyone had previously thought.

The publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species by Natural Selection made evolution a scientifically credible and defensible idea, however, and while he generally avoided the evolution of humans in this work (it being more important to convince readers that evolution has in fact occurred rather than offending religious sensibilities of the time head-on), he later addressed the issue directly in The Descent of Man. Darwin writes in the Summary;

Man may be excused for feeling some pride at having risen, though not through his own exertions, to the very summit of the organic scale; and the fact of his having thus risen, instead of having been aboriginally placed there, may give him hope for a still higher destiny in the distant future. But we are not here concerned with hopes or fears, only with the truth as far as our reason permits us to discover it; and I have given the evidence to the best of my ability. We must, however, acknowledge, as it seems to me, that man with all his noble qualities, with sympathy which feels for the most debased, with benevolence which extends not only to other men but to the humblest living creature, with his god-like intellect which has penetrated into the movements and constitution of the solar system – with all these exalted powers – Man still bears in his bodily frame the indelible stamp of his lowly origin.

A Mandrill as it appears in the 2nd edition of Darwin’s The Descent of Man.

Darwin wasn’t the first to consider that men today had changed from earlier forms, although Darwin was much closer to the truth than other intellectual peers. The Ionic philosopher Anaximander proposed an idea that later would come back, in new form, as the Aquatic Ape Hypothesis. In his valuable book From the Greeks to Darwin, Henry Fairfield Osborn presents Anaximander’s thesis thusly;

He conceived of the earth as first existing in a fluid state. From its gradual drying up all living creatures were produced, beginning with men. These aquatic men first appeared in the form of fishes in the water, and they emerged from this element only after they had progressed so far as to be able to further develop and sustain themselves upon land. This is rather analogous development from a simpler to a more advanced structure by a change of organs, yet a germ of the Evolution idea is found here.

We find that Anaximander advanced some reasons for this view. He pointed to a man’s long helplessness after birth as one of the proofs that he cannot be in his original condition. His hypothetical ancestors of man were supposed to be first encased in horny capsules, floating and feeding in water; as soon as these ‘fish-men’ were in a condition to emerge, they came on land, the capsule burst, and they took their human form.

After evolution became established in both terms of fact and theory, the great fossil collectors of the late 19th and early 20th century began to come up with hypotheses as to from whence came Homo sapiens. In his Neo-Lamarckian 1896 treatise, Edward Drinker Cope proposed the following hypothesis;

The relation of this fact [“the high percentage of quadritubercular superior molars in the Malays, Polynesians, and Melanesians”] to phylogeny is to confirm Haeckel’s hypothesis of the lemurine ancestry of man. I have advanced the hypothesis that the Anthropomorpha (which include man and the anthropoid apes) have been derived directly from the lemurs, without passing through the monkeys proper. This close association of man with the apes, is based on various considerations.

Cope goes on to list some of the differences, focusing primarily on limbs and teeth, before coming to this passage;

Professor Virchow in a late address has thrown down the gage to the evolutionary anthropologists by asserting that “scientific anthropology begins with living races,” adding “that the first step in the construction of the doctrine of transformism will be the explanation of the way the human races have been formed,” etc. But the only way of solving the latter problem will be by the discovery of the ancestral races, which are extinct. The ad captandum remarks of the learned professor as to deriving an Aryan from a Negro, etc. remind one of the criticisms directed at the doctrine of evolution when it was first presented to the public, as to a horse never producing a cow, etc. It is well known to Professor Virchow that human races present greater or less approximations to the simian type in various respects… Professor Virchow states that the Neanderthal man is a diseased subject, but the disease has evidently not destroyed his race characters; and in his address he ignores the important and well-authenticated discovery of the man and woman of Spy. These observations are reinforced by recent discovery of a similar man by DuBois at Trinil in the island of Java [“Java Man,” otherwise known as Pithecanthropus erectus].

The second part of the original “March of Progress” from F. Clark Howell’s Early Man

Cope goes on to describe the fossils, noting that the remains DuBois had found do not seem to be of a Neanderthal, and Neanderthals are sufficiently far from humans that Cope finds the scientific name Homo neanderthalensis somewhat objectionable, the more defining characteristics of Neanderthals being found nowhere in the aboriginal peoples then known. Nowhere does Cope suggest an anagenic relationship of Neanderthals or “Java Man” as a direct ancestor, although their utility in showing evolution has occurred is invaluable. Still, the fossil remains of hominids (and in turn, their ancestors) were certainly wanting during Cope’s time, but in the first half of the 20th century some scientists became to come across some bonanzas in Africa. Raymond Dart was one of the most noted scientists to study the great fossil-bearing caves from Taung, Sterkfontein, and Makapansgat in South Africa. In the fantastic book The Hunters of the Hunted?, C.K. Brain shares with us this passage of Dart’s from his early discoveries in the caves;

The fossil animals slain by the man-apes at Makapansgat were so big that in 1925 I was misled into believing that only human beings of advanced intelligence could have been responsible for such manlike hunting work as the bones revealed… These Makapansgat protomen, like Nimrod long after them, were might hunters.

They were also callous and brutal. The most shocking specimen was the fractured lower jaw of a 12-year-old son of a manlike ape. The lad had been killed by a violent blow delivered with calculated accuracy on the point of the chin, either by a smashing fist or a club. The bludgeon blow was so vicious that it had shattered the jaw on both sides of the face and knocked out all the front teeth. That dramatic specimen impelled me in 1948 and the seven years following to study further their murderous and cannibalistic way of life.

As Brain then notes, such was the murderous Australopithecus of R. A. Dart; brutal savages and cannibals, making their tools and weapons out of the bones and horns of the animals that they managed to kill. Examinations of the cave after Dart, however revealed something incredibly different from the terrifying reign of the “protomen.” Humans were, in fact, prey for a long time, many remains attributed to cannibalism instead being signs that the caves once belonged to fearsome predators. One of the most famous evidences is part of a skull with two puncture holes, nearly exactly matching the canine teeth of a leopard. Indeed, the real story seems to be a struggle for existence among the hominids found in these areas, not being very advanced in hunting at all. Nonetheless, they eventually overtook the predators (when they weren’t stealing from their kills), and came to reside in the caves themselves. Such revelations, however, would have to wait until the 2nd half of the 20th century, and there were plenty more ideas about human origins prior to Brain’s 1981 book.

Despite the progress of science there have always been “fringe” hypotheses about humans and their place in the universe, and perhaps nothing fueled crackpot claims so much as the popularity of UFOs and the possible existence of aliens on Mars during the first half of the 20th century. Humans became the products of alien engineering projects, bizarre sexual encounters between aliens and early hominids, or even aliens themselves, having no remembrance of coming from a civilization on another planet. Racist hypotheses also abounded, and there were many odd amalgamations of cherry-picked scientific discoveries and superstition.

While some were content to conjure up ideas of aliens laying down with “Lucy”, scientists continued to attempt to determine not only from what ancestors man arose from, but where those ancestors may be. A.S. Romer, in the 1933 book Man and the Vertebrates Vol. I, supports H.F. Osborn’s view that man’s origins were likely to be found somewhere in Asia. Indeed, the famous 1923 expedition undertaken to the Flaming Cliffs of Mongolia by Roy Chapman Andrews that yielded Protoceratops and so many dinosaur eggs was intended to be a search for the ancestors of humans. Romer writes;

The fossil of Tertiary tropical life is, however, still comparatively unknown. It is not only possible but extremely probable that the Asiatic hills will, upon further exploration, give us the certain knowledge we desire of the primate ancestors of man.

Despite the lack of early ancestors, however, there was enough scientific understanding for Romer to close out the 1st volume with the following words;

Man has gone far and, we trust, may go still farther along the lines of evolution. But in his every feature – brain, sense organs, limbs – he is a product of primitive evolutionary trends and owes, in his high estate, much to his arboreal ancestry, to features developed by his Tertiary forefathers for life in the trees.

Romer’s diagram of human evolution varies from that described by Cope earlier, however. While Cope saw humans evolving directly from lemur-like ancestors, Romer created a diagram of extant primates (lemurs, tarsiers, new world monkeys, old world monkeys, great apes, and man) connected by one line, each of the groups branching off from the main line leading to man and seemingly having no relation to each other. This is part of the classic model of anagenesis that seems to suggest non-stop progress to man, almost as if a vitalistic force was setting humans on a fast-track (although I am not suggesting Romer had this view or advocated it; it merely seems to be an underlying theme in such illustrations). As G.G Simpson noted in the 1950 popular work The Meaning of Evolution, however, contentious fossil remains so close to humans can easily stir up trouble;

Primate classification has been the diversion of so many students unfamiliar with the classification of other animals that it is, frankly, a mess. It involves matter of opinion on human origins and, humans being what they are, such opinions are endlessly varied and not always distinguished by competence or logic.

G.G. Simpson’s tree diagram of primate evolution, from the 3rd edition of The Meaning of Evolution.

Simpson’s diagram of primate evolution is a bit closer to truth than Romer’s from nearly 20 years earlier, as well. It more closely resembled the “branching bush” of evolution, groups linked by common ancestors with some lineages dying out and leaving no living descendants. Still, great apes are distinguished from “early man” and the genus Homo, and given that details are not given it can’t be ascertained whether Simpson held the view that all hominids discovered by that time were linked in a straight-line of evolution. Edwin H. Colbert (also of the American Museum of Natural History), put forth a similar view in his popular work Evolution of the Vertebrates, stating;

Even though human beings may not be descended from the australopithecines as we know them, it is very possible that man arose from australopithecine-like ancestors. The origin of the human stock probably occurred in late Tertiary times, for man is essentially a Pleistocene animal. Having become differentiated from his primate relatives, man evolved during the Pleistocene period along certain lines that made him what his is today. The evolutionary development of human beings was not of great magnitude within the course of Pleistocene history; rather it was a matter of the perfection of details that set man apart from all other primates, and from all other animals for that matter.

The hominid reconstructions as they appear in Colbert’s Evolution of the Vertebrates.

This isn’t an especially profound statement, more along the lines of “Man is different from other animals, thus different things must have happened to cause his ‘perfection,'” but it does point towards the “ladder” view of human evolution. What Colbert is essentially saying is during the latest parts of human evolution, there was a refinement of types rather than major evolutionary change, and while he doesn’t line up a point-by-point lineage some of the pictures accompanying his text do suggest a sort of anagenesis from Australopithecus to Pithecanthropus to Neanderthals to Homo sapiens. Chris Beard, in his indispensable book The Hunt For the Dawn Monkey, attributes this view of human evolutionary “progress” to Sir Wilfrid E. Le Gros Clark, quoting Clark’s work The Antecedents of Man as follows;

Among the Primates of today, the series tree shrew-lemur-tarsier-monkey-ape-man suggests progressive levels of organization in an actual evolutionary sequence. And that such a sequence did occur is demonstrated by the fossil series beginning with the early plesiadapids [so-called “archaic primates” from the Paleocene] and extending through the Palaeocene and Eocene prosimians, and through the cercopithecoid [Old World monkeys] and pongid [apes] Primates of the Oligocene, Miocene, and Pliocene, to the hominids of the Pleistocene. Thus the foundations of evolutionary development which finally culminated in our own species, Homo sapiens, were laid when the first little tree shrew-like creatures advanced beyond the level of the lowly insectivores which lived during the Cretaceous period and embarked on an arboreal career without the restrictions and limitations imposed by… a terrestrial mode of life.

Skeleton of a Potto (a prosimian like a Loris) from the American Museum of Natural History

As Beard notes in his book, however, most of the hominid fossils then known were almost like bookends to a series, with the lemur-like ancestors (i.e. Notharctus from North America and Adapis from France) of later primates and the famous African and European hominids being the most well known. As countries became more open to science, however, more and more fossils came out of the ground, and Beard does note that while Africa may very well be the “cradle of humanity” in terms of hominids, if you really want to go back to the beginnings of prosimians Asia is the place to search. This somewhat vindicates those who thought that Asia would be the place to look for human ancestors, though not quite in the way they imagined. Even so, the ladder view seemed to be the favored one, at least for all fossil hominids younger than the Australopithecus. In his Vertebrate Paleontology (3rd Edition), A.S. Romer writes;

A word may be added here with regard to the nomeclature of human finds. We have freely used several generic terms for various early human finds. Such a usage implies that the forms differed widely from one another, had independent evolutionary histories, and did not interbreed – that the differences between them were not merely of species value but of such a magnitude as, for example, those between a cow and an antelope, a dog and a fox. This is absurd. Because they are so close to us, we tend to magnify differences. Actually, the differences between modern man and “Pithecanthropus” are, viewed impersonally, rather minor ones (particularly if we keep in mind the considerable variations found even today), and quite surely all types on the human line above the Australopithecus level pertain to our own genus Homo. Further, while communications between the various Old World area in which man was early present were obviously poor, and there presumably was little interbreeding and consequently (as today) a tendency for the differentiation of regional races, it seems fair to assume that throughout our long Pleistocene history, our human ancestors formed at all stages a single, if variable, group.

Despite this rather homogenous view of human evolution (the idea that Pithecanthropus falls within human variation being an idea that has reared its ugly head in modern creationism, as we’ll see later), Romer does make a distinction when it comes to Neanderthals. He writes;

A type of man definitely assignable to our own species, Homo sapiens, appeared in Europe well toward the end of the last glaciation, not more than 50,000 years or so ago. One would at first assume that he had arisen from his Neanderthal predecessor. But the contrasts are too great; there in (in Europe, at least) no evidence of transitional types; the appearance of modern man was, the evidence suggests, relatively sudden. There is every indication that the “modernized” invaders wiped out their predecessors (Tasmania is a modern parallel).

The third part of the original “March of Progress” from F. Clark Howell’s Early Man

Thus, during the 1960’s the evolution of man was rather ladder-like as it approached culmination, with relatively little radiation of types. The links to Australopithecus and Homo neanderthalensis as understood then were both doubted, although it was certain that humans had gone through a similar stage in the evolutionary process from the apes. Indeed, the ladder-view seemed to use representative types to show the gradation of evolution than linking all known hominids into a straight line (at least this is the impression from the popular works cited). Still, visual representations of human ancestry seemed far-more powerful than the actual text of many of these books, which brings us to the (in)famous “March of Progress.” The artwork, appearing in the 1979 Time-Life book Early Man by F. Clark Howell, certainly became iconic, and I am lucky enough to have a copy of the “Young Readers Nature Library” version of the book from my childhood. The “march,” with all members standing upright, carries this caption, and proceeds as follows;

The stages in man’s development from an apelike ancestor to the modern human being are shown in drawings on this and the following three pages. Some of the stages have been drawn on the basis of very little evidence – a few teeth, a jaw or some leg bones. However, experts can often figure out a great deal about what a whole animal looked like from studying these few remains. In general, man’s ancestors have grown taller as they became more advanced. For purposes of comparison, this chart shows all of them standing although the ones on this page [Pliopithecus through Oreopithecus] actually walked on all fours.

Pliopithecus – Proconsul – Dryopithecus – Oreopithecus – Ramapithecus – Australopithecus africanus – Australopithecus robustus – Australopithecus boisei – Homo habilis – Homo erectus – Early Homo sapiens – Neanderthal Man – Cro-Magnon Man – Modern Man

The final part of the original “March of Progress” from F. Clark Howell’s Early Man

Skull of Proconsul from the American Museum of Natural History

The inclusion of “Early Homo sapiens” before “Neanderthal Man” is a strange one, and even on the following pages australopithecines are shown living during the same time or exhibiting variation. While the author and artists of the book may not have meant to show that all the primates in their line evolved directly from their predecessors in line, the power of the image overwhelmed any explanation, and the image certainly became iconic. Evolutionary scientists did not sit idly by while a fallacious notion of human evolution was promulgated, however; Stephen Jay Gould opens his 1989 book on the Cambrian fauna Wonderful Life with his astonishment that his books, translated into other languages, bear the incorrect image. Gould writes;

The march of progress is the canonical representation of evolution – the one picture immediately grasped and viscerally understood by all. This may best be appreciated by its prominent use in humor and in advertising. These professions provide our best test of public perceptions. Jokes and ads most click in the fleeting second that our attention grants them. …

Life is a copiously branching bush, continually pruned by the grim reaper of extinction, not a ladder of predictable progress. Most people may know this as a phrase to be uttered, but not as a concept brought into the deep interior of understanding. Hence we continually make errors inspired by unconscious allegiance to the ladder of progress, even when we explicitly deny such a superannuated view of life. …

First, in an error that I call “life’s little joke”, we are virtually compelled to the stunning mistake of citing unsuccessful lineages as classic “textbook cases” of “evolution.” We do this because we try to extract a single line of advance from the true topology of copious branching. In this misguided effort, we are inevitably drawn to bushes so near the brink of total annihilation that they retain only one surviving twig. We then view this twig as the acme of upward achievement, rather than the probable last gasp of richer ancestry.

Gould as absolutely right; the iconic imagery of the “March” is so wrong, yet so easily understood, that it survives even when it is inaccurate. Creationists use it as a symbol of evolution (or, more often, mistakes evolutionary scientists have made), while satirists often use it to show the “devolution” of one group or another, and I doubt that the overall imagery will lose its utility anytime soon. If nothing else, the lesson we must learn from “The March of Progress” is that we are to use the utmost care in selecting visual representations of evolution, for one image can stay in the collective understanding (or misunderstanding) of a subject even when it’s accuracy has long passed the expiration date.

Going back to the thoughts of human evolution during the 60’s and 70’s, the life of earlier hominids was deemed to be a violent one, centering around man as the hunter. Without the ability to hunt as a group on dangerous African plains, we wouldn’t have advanced to our current state, requiring plenty of red meat to provide human ancestors more protein for their growing brains (or so was the logic, anyway). Some people, however, didn’t buy into this view that humans owe everything that evolution bestowed upon them to the Great Hunter, and so a feminist reaction was proposed; the Aquatic Ape Hypothesis. Centuries after Anaximander proposed his own views on the aquatic nature of man, Alister Hardy presented a lecture on “Aquatic Man: Past, Present, and Future” in 1960, and soon after he presented the idea to the public in a series of articles for New Scientist magazine.

The Aquatic Ape Hypothesis did not really take off, however, until a writer named Elaine Morgan published the book The Descent of Woman in 1972. Hardly a scientific work, the book focused more on a rejection of male-centered anthropology, and Donna Kossy provides an excerpt of Morgan’s prose in the book Strange Creations;

She knew at once she wasn’t going to like it there. She had four hands better adapted for gripping than walking and she wasn’t very fast on the ground. She was a fruit eater and as far as she could see there wasn’t any fruit… She never thought of digging for roots – she wasn’t very bright. She got thirsty, too, and the water holes were death traps with large cats lurking hopefully around them. She got horribly skinny and scruffy-looking.

…The only thing she had going for her was the fact that she was one of a community, so that if they all ran away together a predator would be satisfied with catching the slowest and the rest would survive a little longer.

What then, did she do? Did she take a crash course in walking erect, convince some male overnight that he must now be the breadwinner, and back him up by agreeing to go hairless and thus constituting an even more vulnerable and conspicuous target for any passing carnivore? Did she turn into the Naked Ape?

Of course, she did nothing of the kind. There simply wasn’t time. In the circumstances, there was only one thing she could possibly turn into, and she promptly did it. She turned into a leopard’s dinner.

…

With piercing squeals of terror she [a different ancestral ape] ran straight into the sea. The carnivore was a species of cat and didn’t like wetting his feet; and moreover, though he had twice her body weight, she was accustomed like most tree-dwellers to adopting an upright posture, even though she used four legs for locomotion. She was thus able to go farther into the water than he could without drowning. She went right in up to her neck and waited there clutching her baby until the cat got fed up with waiting and went back to the grasslands…

…One idle afternoon after a good deal of trial and error she picked up a pebble – this required no luck at all because the beach was covered with thousands of pebbles – and hit one of the shells with it, and the shell cracked. She tried it again, and it worked every time. So she became a tool user, and a male watched her and imitated her (This doesn’t mean that she was any smarter than he was – only that necessity is the mother of invention. Later his necessities, and therefore his inventiveness, outstripped hers.)

… She began to turn into a naked ape for the same reason as the porpoise turned into a naked cetacean, the hippopotamus into a naked ungulate, the walrus into a naked pinniped, and the manatee into a naked sirenian.

Morgan wrote other books on the subject and there still is a bit of a following to the idea that humans arrived in their current configuration due to an “aquatic stage” sometime in their history. Long hair on the head is for babies to cling to, large breasts float better than small ones, hairlessness makes one more streamlined, and nearly any part of the body that has been adapted this way or that, is potentially explained by life in or around the water, and even recent popular science books have taken a bit of a shine to Morgan’s hypothesis (like Survival of the Sickest). Despite the popular appeal, there is not much to the hypothesis, however, and no actual evidence to confirm it, fossil or otherwise. Indeed, it almost starts with modern female anatomy and works backwards, trying to find an explanation for this trait or that, based upon how we act in the water now, although if we were ever well-adapted to life in the sea we have lost such abilities. While Morgan was right to criticize the lack of attention given to women in terms of anthropology and evolution, her view is as extreme (if not moreso) than the one she was trying to replace.

And now we come to the present. The evolution of Homo sapiens from older species now extinct has long been established, the evolutionary history of hominids now understood to represent more of a “bush” than a ladder of progress. There are lineages that do show anagenesis or transitions from one species to another, but in the last few decades so many unexpected finds have come out of the ground that imagining human evolution to be a straight-line, deigned to produce us in our present form, is utterly ridiculous. There are still battles to be fought over which fossil fits where, what kind of dispersal early hominids had, what pressures led to our ancestors being obligate bipeds, but the competing hypotheses in such debates become more and more refined with every discovery, and the evidence supporting the fact that we have evolved cannot be overturned. This isn’t to say, however, that some trends in understanding ourselves or our ancestry haven’t changed. As I mentioned earlier, some of the diagrams of human evolution during the first half of the 20th century based themselves on living primates and prosimians, looking to them for the order in which we should place human evolution. There has been something of a return to this as of late, but in the area of evolutionary psychology rather than paleoanthropology. Chimpanzees and bonobos, after being confirmed as our closest living relatives, are often used as the two polar archetypes for our own ancestry; we were either violent like chimpanzees, horny bohemians like bonobos, or something in-between. While it is often noted that we humans have the ability to do good in spite of our evolutionary past, the authors of Demonic Males make their premise clear; all living male apes are exceedingly violent;

This helps explain why humans are cursed with demonic males. First, why demonic? In other words, why are human males given to vicious, lethal aggression? Thinking only of war, putting aside for the moment rape and battering and murder, the curse stems from our species’ own special party-gang traits: coalitionary bonds among males, male dominion over an expandable territory, and variable party size. The combination of these traits means that killing a neighboring male is usually worthwhile, and can often be done safely.

Frans de Waal, in Our Inner Ape, also recognizes our dark side, but is more of an optimist; he sees the sexual (and “peaceful”) culture of bonobos to be proof that violence is not pre-ordained for us. He writes;

That such a creature could have been produced through the elimination of unsuccessful genotypes is what lends the Darwinian view its power. If we avoid confusing this process with its products – the Beethoven error – we see one of the most internally conflicted animals ever to walk the earth. It is a capable of unbelievable destruction of both its environment and its own kind, yet at the same time it possess wells of empathy and love deeper than ever seen before. Since this animal has gained dominance over all others, it’s all the more important that it takes an honest look in the mirror, so that it knows both the archenemy it faces and the ally that stands ready to help it build a better world.

While chimpanzees and bonobos are our closest living relatives, we proceeded on our own line of evolution for at least 4,000,000 years, evolving on an apparently accelerated trajectory while our evolutionary “cousins” have not been adapted in exactly the same way. This is not an appeal to say that humans are so distinct that we should not look to living primates for answers about why we are as we are, but rather that we must also keep the long view in perspective. Exclusively using the behavior of living apes to work backwards to the behavior of our own ancestors treats the subject as if chimpanzees and bonobos our are ancestors, one of the biggest mistakes still made by people unfamiliar with how evolution works. Speaking of the “If we’re evolved, why are there still monkeys?” argument, it is now time to look at modern creationism and its view of human evolution.

As covered at the beginning of this post, the contradictory Genesis accounts tell of humans being created at some point in the past by the Judeo-Christian God, exactly when this event occurred being inferred from chronologies in the Bible. Still, how could such stories stand up to the weight of scientific evidence for our own evolution? The truth of the matter is that it cannot, but that has not stopped some from trying to bring us back to a reliance on Genesis. The first unsuccessful attempt to debunk human evolution I came across was in Jonathan Wells’ odious work Icons of Evolution, which bears a scaled-down version of the “March of Progress” on its cover. In the chapter discussing this particular “icon”, Wells notes that he is familiar with Gould’s rejection of the ladder-view of human evolution in Wonderful Life, but this does not seem to be sufficient for Wells. He engages in the following rhetoric in trying to make his case;

But how does Gould know that extinctions are accidents? On the basis of fossil evidence, how could he possibly know? Clearly, it takes more than a pattern in the fossil record to answer sweeping questions about direction and purpose – even if we knew for sure what those patterns are. And even if extinctions are accidents, does that rule out the possibility that evolution is goal-oriented? Everyone’s death is contingent; does that make everyone’s birth and life an accident? The continued existence of the human species is contingent on many things: That we don’t blow ourselves up with nuclear weapons, that the earth isn’t struck by a large asteroid, and that we don’t poison our environment, among other things. But it doesn’t follow that our very existence is an accident, or that human life is purposeless.

In this metaphysical muddle Wells offers up no evidence that extinctions have a purpose, that evolution is goal-oriented, or that human life has an inherent “purpose.” Indeed, he acts with such incredulity that he seemingly expects it to be contagious, luring the reader in with a string of absurd questions. There is no sign of evolution (or extinction) occurring as a part of a plan or having an ultimate goal and mind, and even if there was some sort of “directing force” to evolution it would seem to be an awfully wasteful process, never ensuring the permanence of a species (and would evolution, therefore, have an end?). What Wells essentially does is dress up Gould’s argument from Wonderful Life as a straw man, and apparently he doesn’t realize that Gould beat him to the punch about the famous illustration (and much more accurately, too) over a decade before Wells published his own book.

Young Earth Creationist ministries, like the well-known Answers in Genesis, take a slightly different approach; goading based upon the perceived authority of the Bible. In his tract The Lie, AiG leader Ken Ham includes cartoon after cartoon of the Bible being set up as the foundation for everything Christians believe, evolution being (often comically) set up as the origins of murder, abortion, and all sin. According to this view, even Old Testament figures like King David fell under the “evil influence” of evolution when they committed various sins, even though Darwin would not even be born until centuries later. The book states;

Society depends on moral foundations. By a mutual agreement which has sometimes been called a “social contract,” man, in an ordered and civilized society, sets limits to his own conduct. However, when such obligations are repudiated and the law collapses along with the order it brings, what option has the man who seeks peace? The psalmist is looking at the fact that whenever the foundations of society are undermined, then what have good and righteous men done to prevent its impending collapse?

Indeed, AiG sets the stakes high; nothing less than the existence of “civilized” and moral society rests on the battle being fought over evolution by creationists. Even those who accept evolution and are Christians are deemed to be compromisers, and generally looked down upon despite shared central theological beliefs. While the argument that there can be no morality without religion is certainly fallacious, it is a powerful concept, deeply tied to the evangelical desire to “save” those who have not accepted Jesus as God. What is even more surprising, however, is that creationists often state this weakness in their thought process up front; in the Young Earth Creationist view, nothing can contradict the Bible, and so anything that seems contradictory to accepted doctrine (which has, of course, been interpreted from the Bible by people) has to either be shoved into the Bible or dismissed as a lie or hoax. Case in point; AiG’s new geologist Andrew Snelling once tried to address the lack of human remains intermingled with those of dinosaurs and other fossil creatures from ages past (they should have been mixed together by the Flood) by stating that God made sure that no human remains survived the Flood so they would not be worshiped if found by subsequent generations of survivors. He wrote;

It would seem to us unloving of God to execute such relentless judgment, but such is God’s abhorrence of sin that its penalty must be seen for what it is—utter destruction and removal of all trace. If God cannot tolerate sin (His holiness cannot ‘look’ on sin), then all trace of sin has to be removed in judgment, which necessitates utter destruction. Should human remains have been allowed to survive the Flood as fossils, then there could also have been the possibility of such remains being worshiped and revered.

But what about the hominid remains that we do find? These are usually said to be “degenerate” people dispersed from the Tower of Babel, as God confused the languages of the people trying to build a tower to reach to heaven and dispersed them, feeling excessively threatened by the attempt for some reason (it is likely that those who wrote the Babel story thought God lived on the firmament in the vault of heaven, a place that actually could be reached if you just built high enough). It has even been argued that if you were to see a Neanderthal today on a subway, you would probably think them a boxer or wrestler, never being the wiser to the fact that you’re looking at another species. Generally members of the genus Homo are incorporated into such arguments, with the more basal Australopithecus and Paranthropus being relegated to merely being “apes.” In The Amazing Story of Creation From Science and the Bible, creationist-celebrity Duane Gish writes;

However, evolutionists’ faith in their theory makes it necessary for them to believe that a tooth, or a piece of skull, or a jawbone, or some other fossil bone came from a creature partway between ape and man. When all of the evidence is carefully and thoroughly studied by the best scientific methods, however, it turns out that these fossils were either from monkeys, apes, or people, and not from something that was part ape and part human.

This assertion is importance not only because it shows the YEC need to shoe-horn various hominids into the three categories mentioned above, but also because it involves one of creationism’s big tricks; trying to equate science with religion. If scientists can be said to “believe” in evolution, or have “faith” that more fossils will be found, then it becomes easy to make it sound like a parallel belief system to Christianity, evolution just being a secular creation myth. This, of course, is far from the truth, but many are easily drawn into this idea as all religions that are not Christian must therefore be incorrect by definition, once again putting the cart before the horse when considering the natural world. Young Earth Creationists aren’t the only ones attempting to refute evolution, however. Hugh Ross is a famous Old Earth Creationist, and his hypotheses are neither here nor there. Rejecting both evolution and the idea that the earth is less than 10,000 years old, Ross holds that Adam and Eve really were created by God just like the Bible says, only 7,000 to 60,000 years ago. As for other hominids, Ross puts them in a separate category with other animals, the primarily dividing factor being a lack of a relationship with God. In The Genesis Question Ross writes;

Although bipedal, tool-using, large-brained primates roamed Earth for hundreds of thousands (perhaps a million) years, religious relics date back only about either thousand to twenty-four thousand years. Thus, the anthropological date for the first spirit creatures agrees with the biblical date.

Thought most anthropologists still insist that the bipedal primates were “human,” the conflict lies more in semantics than in research data. Support for their views that modern humans descended from these primate species is rapidly eroding. Evidence now indicated that all bipedal primates went extinct, with the possible exception of Neanderthal, before the advent of human beings. As for Neanderthal, the possibility of a biological link with humanity has been conclusively ruled out.

Only such Neanderthal/Homo sapiens interactions, however improbable, haven’t been conclusively ruled out. There are strong arguments from both sides, and at present it doesn’t appear that we’ll be able to come up with a definitive answer. Still, Ross’ stance is just as silly as that of the YEC’s; he concedes scientific evidence for an old earth and universe, yet evolution is still too much of a detestable idea to be taken seriously. It’s not surprising that AiG issued a book, twice the length of Ross’ original, entitled Refuting Compromise, presenting a point-by-point breakdown of Ross’ arguments. All this is a great waste of intellect and paper, but I’m sure Jonathan Sarfati and Hugh Ross would say the same about what I’m doing here.

There is still at least one more trick in the creationist toolkit, however; bringing up past hypotheses that have been refuted or fossil lineages that have been changed and claiming that scientists are either ignorant or liars. Such is the setup provided to Jonathan Wells by the apologist Lee Strobel, who prides himself on being a “Devil’s Advocate” when he actually presents those he interviews with straw man after straw man. In the numbingly boring book The Case for a Creator, Strobel concocts a story of how he was convinced that evolution was true because of a reconstruction of “Java Man” (whom we’ve already met, see above), only to have Jonathan Wells crush his childhood memories of Pithecanthropus. he writes;

As I leaf back through my time-worn copies of the World Book from my childhood, I can now see how faulty science and Darwinian presuppositions forced my former friend Java man into an evolutionary parade that’s based much more on imagination than reality. Unfortunately, he’s not the only example of that phenomenon, which is rife to the point of rending the record of supposed human evolution totally untrustworthy.

I guess Strobel couldn’t be bothered to update himself on evolutionary theory between the time he received his World Book and when he met Wells, and if his “faith” in a topic can be so easily manipulated, I wonder why anyone considers him a good apologist. Still, creationists continue to bring up historical mistakes like “Nebraska Man” as if such errors were to strike terror into the hearts of scientists everywhere. Outside of the outright lies, however, Strobel’s prose shows us another important side to creationist tactics in trying to undermine evolution; science is not to be trusted at all. This strategy, like those mentioned before, works because it appeals to sentiments probably already held by many evangelicals, primarily that the Bible is the source of all truth and holds the answer to every conceivable question, any sort of knowledge or understanding produced by man being inherently flawed and untrustworthy. The fact that the Bible requires interpretation and that theology is constantly changing, however, does not seem to register, and so the evolution of humans is denied simply because the idea is unsavory.

And that, my friends, bring this post to a close. Despite the amount of resources I’ve used from my personal library, this is hardly an exhaustive study; I have largely ignored major fossil finds in order to focus on the ideas surrounding our own evolution, and any more detail would have greatly prolonged this post. What I hope to have shown, however, is that science does not crumble when taxa are reassigned or a new fossil shows up where it was not expected; it only furthers our understanding. If a hypothesis is shown to be false, then that is one more thing that we now understand to be wrong, therefore improving our knowledge and understanding. Some will continue to consider this a source of weakness, but as we are not gods, the constant desire to improve our understanding of nature is the best that we can hope for, and the correction of old ideas is what science thrives on. What would be the alternative? To hold on to favored ideas even when they’ve been proven wrong, hoping that the mere devotion to a notion would make it true? Such an idea is far from being unproductive; it is dangerous. Fossil finds will continue to be made, the genome will continue to be searched for clues to our evolution, and scientists will continue to ask questions, being both amazed but never satisfied by the latest information as to the history of life on earth.

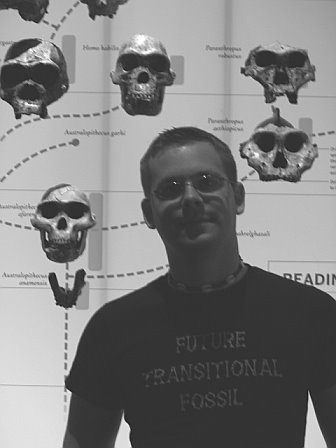

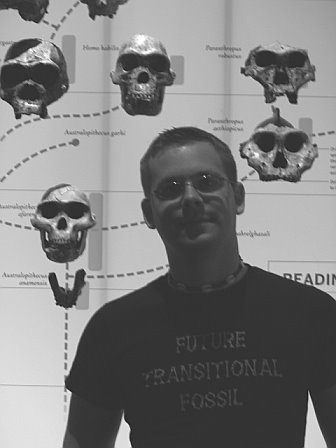

The author taking his place among the transitional forms in the branching bush that is hominid evolution, taken at the American Museum of Natural History.

Recent Comments